Alex Karp Insists Palantir Doesn’t Spy on Americans. Here’s What He’s Not Saying.

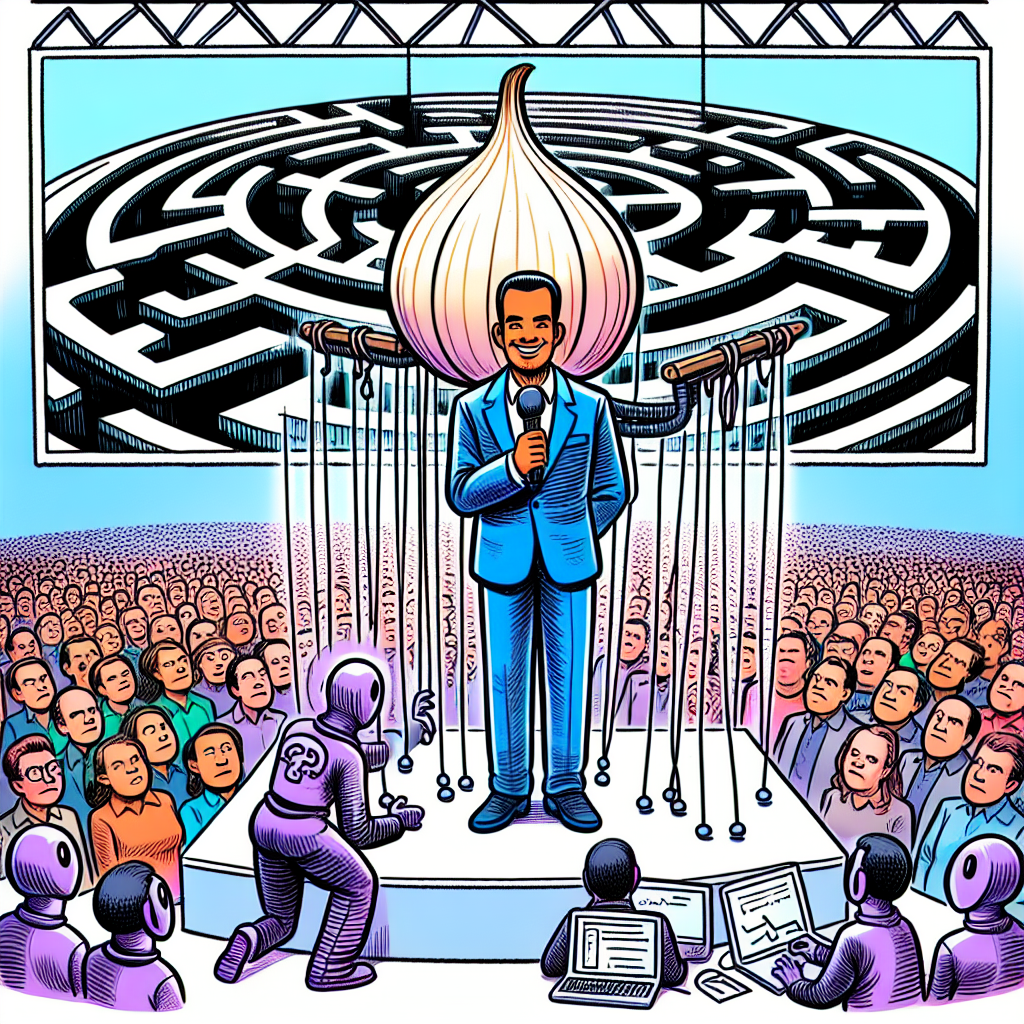

In an era where digital oversight verges on the omnipresent, the proclamations of Palantir CEO Alex Karp merit rigorous scrutiny—lest we fall prey to the comforting sophistry that something is not happening simply because it is not being openly acknowledged. The recent avowal by Karp that Palantir does not “spy” on Americans is a facile reassurance that conveniently skirts the labyrinthine realities of modern surveillance capitalism, state collaboration, and algorithmic opacity. This delicate dance between denials and the obfuscation of data practices demands a more erudite and penetrating examination, lest we conflate public relations rhetoric with empirical truth.

To dissect this matter with the gravitas it deserves, one must first invoke the timeless principle elucidated by Cicero—“O tempora! O mores!” (“Oh the times! Oh the customs!”). The very fabric of contemporary society has been rewoven with threads of data collection and algorithmic scrutiny. Palantir, the avant-garde firm specializing in integrative data analytics for intelligence and law enforcement, occupies a pivotal nexus in this infrastructural edifice. While Karp’s outright repudiation of “spying on Americans” may placate the lay observer, the Snowden revelations have already indelibly demonstrated the extent to which Palantir’s technological capabilities have been deployed by the NSA and other agencies under exemptions that render the average citizen’s privacy a secondary consideration.

It is imperative, therefore, to elucidate what Karp is not saying, for oftentimes silence or euphemistic linguistics bear heavier weight than categorical denials. The assertion that Palantir does not directly engage in spying glosses over the intricate ecosystem in which Palantir’s software operates—not merely as a passive tool but as an active agent enabling mass surveillance. As Lex Machina would counsel, “acta non verba” (deeds, not words)—Palantir’s technology is implicated in the aggregation, cross-referencing, and predictive analysis of personal data, often without transparent oversight. This is surveillance's essence, effectuated via code rather than cloak-and-dagger espionage.

Moreover, one must consider the legal and philosophical nuance surrounding the interpretation of “spying.” The jurisprudence and semantic parameters of surveillance activities are evolving in a manner that often purposefully circumvents public understanding and democratic consent. Palantir’s contracts with federal and local agencies frequently include clauses for data ingestion that indirectly lead to the monitoring of individuals within the United States, under the guise of national security or crime prevention. In this Orwellian tableau, “spying” becomes a euphemism for normalized invasions of privacy, camouflaged beneath layers of bureaucratic jargon.

Another salient facet is the interplay between private enterprise and government intelligence apparatuses—a symbiotic relationship that merits a Diogenes-like spotlight. Palantir’s commercial success is inextricably linked to its ability to adapt its sophisticated algorithms to the exigencies of federal agencies tasked with intelligence and counterterrorism. Such relationships do not allow for a clean disentanglement of corporate self-regulation or moral high ground. This is a shadowy nexus where ethics often bow to pragmatism, and the citizenry becomes ancillary to data harvesting imperatives.

Furthermore, the notion that “Palantir doesn’t spy on Americans” betrays a reductive worldview that binary-verifies the presence or absence of surveillance. This all-or-nothing paradigm fails to capture the decentralized, distributed, and cooperative nature of contemporary spying. Palantir’s platforms often serve as the connective tissue linking multiple databases, piecing together digital dossiers whose scale and depth far exceed traditional conceptions of surveillance. The insidiousness lies in the normalization of such practices; each piece of data becomes a brushstroke in a constantly evolving portrait of suspicion, curated without citizen knowledge or recourse.

One might invoke the wisdom of Tacitus, who famously asserted, “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” (“Who watches the watchers?”). In a system where firms like Palantir wield immense power over informational flows, and where accountability mechanisms remain nebulous at best, the prospect of unchecked surveillance is not a paranoid fancy but an inevitable corollary. It behooves us not only to question explicit declarations of innocence but to demand transparency regarding the architecture and application of surveillance tools.

Finally, the public discourse surrounding Palantir and similar entities is often suffused with a patina of techno-optimism that frames data analytics as a panacea for security and governance issues. Such epiphanic idealism obscures the fundamental trade-offs between liberty and security, subjectivity and objectivity, privacy and efficiency. The issue at stake is not merely whether Palantir spies on Americans in a traditional sense but whether the fabric of privacy is being systematically unraveled by the imperatives of datafication, commodification, and algorithmic governance.

In conclusion, any audacious claim that Palantir eschews spying on American citizens warrants a dispassionate, forensic analysis beyond the lexicon of public relations. One must navigate the labyrinth of technological capabilities, contractual realities, and sociopolitical imperatives that underpin the contemporary surveillance state. The sophistry of denial is no substitute for vigilance. The imperium of surveillance is not merely a question of “if” but “how,” “where,” and “to what end.” Until such questions are adequately answered, proclamations of innocence remain but rhetorical pyrotechnics shrouding a far murkier reality.