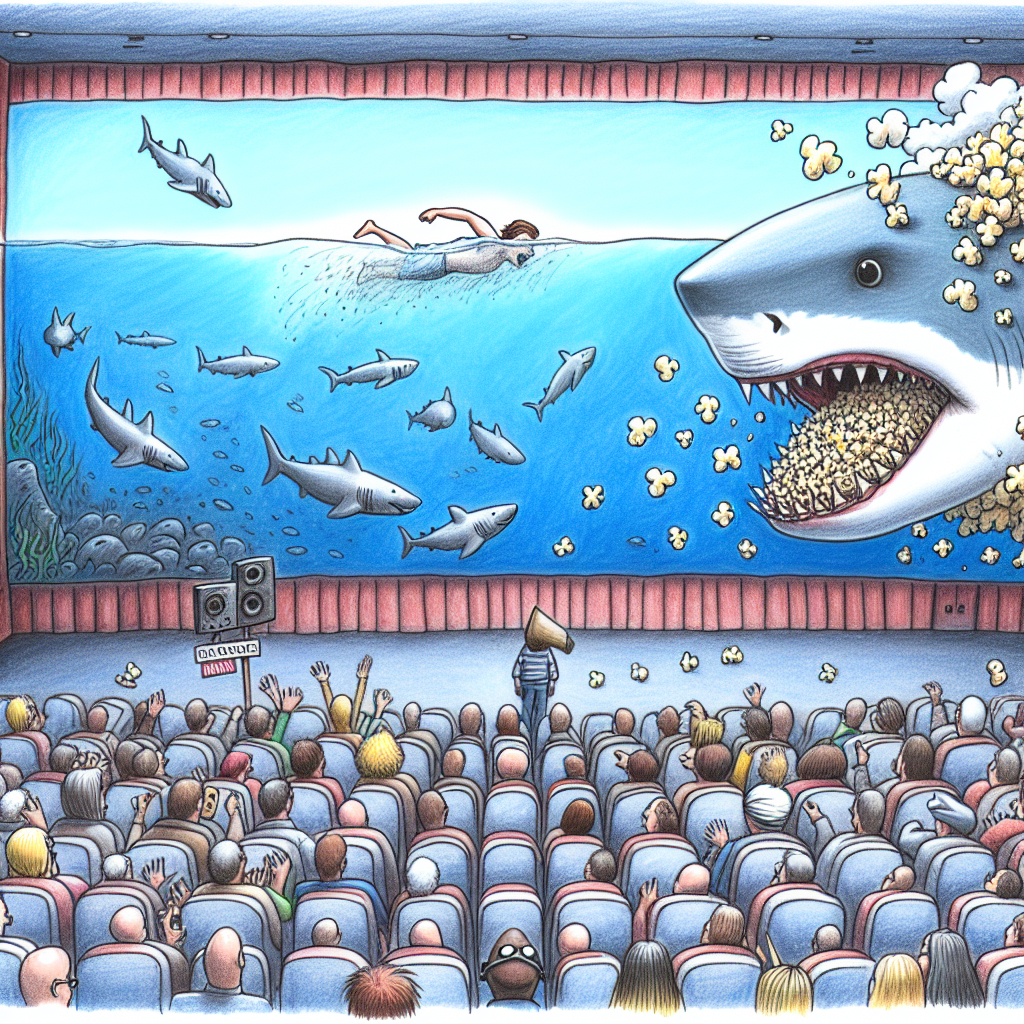

'Jaws' at 50: How a single movie changed our perception of white sharks forever

It’s been half a century since Steven Spielberg’s Jaws first gripped audiences, transforming the cinematic landscape and embedding a cultural paranoia about great white sharks that still echoes today. While many celebrate Jaws as a thrilling masterpiece, its legacy extends far beyond the theater—it reshaped how humanity views one of the ocean’s apex predators in a way that science, journalism, and conservation efforts are still wrestling to undo.

The film distilled the great white shark into an archetype of pure menace, a mindless killer lurking just beneath the waves, preying on unsuspecting swimmers. This depiction, although grounded in selective real-life shark attack incidents, certainly wasn’t an objective reflection of shark behavior, which is complex, variable, and deeply misunderstood. But the power of narrative—especially through the lens of Hollywood’s storytelling—cemented a lasting image of white sharks as villains of the deep. And it’s no exaggeration to say that decades later, the ripple effects of this cinematic caricature still fuel fear, misinformation, and misguided policies.

One cannot discuss this phenomenon without recognizing the psychological and sociological operations behind fear-mongering in pop culture. Fear, as a primal emotional response, heightens engagement and makes stories memorable. The suspenseful build-up, the ominous music, the brutal visuals in Jaws—all conspired to program an ingrained wariness of sharks into the collective consciousness. Over years, this has morphed into a kind of ecological amnesia where the shark's actual ecological role and plight are sidelined in favor of a lurid mythos. This is especially pertinent in an era where white shark populations face severe threats from overfishing, finning, and habitat degradation.

It’s worth asking whether the filmmakers, consciously or unconsciously, activated a feedback loop that did more harm than good. The surge in shark hunting, fueled by public panic post-Jaws, arguably exacerbated population declines that scientists are still trying to recover from. What’s more, even modern media often leans heavily on the “shark attack” narrative because it sells. When sustainable narratives about these creatures are overshadowed by tales of terror, the public’s understanding stagnates or backslides.

But here lies a fascinating paradox: Jaws also triggered curiosity and fascination with sharks at unprecedented levels. Academic research, marine documentaries, conservation initiatives, and public outreach programs gained visibility partly because of the spike in interest the movie generated. People began investing in shark science as an antidote to the fear, probing deeper to unravel complex behaviors—migration patterns, social structures, and environmental importance—that defy the simplistic predator caricature.

And yet, despite these positive offshoots, there remains a persistent cognitive dissonance in public perceptions. How many casually dismiss a white shark as a "bloodthirsty man-eater" while ignoring that shark attacks on humans are exceedingly rare, often the result of mistaken identity rather than malicious intent? The scientific community attempts to disseminate data—sharks rarely target humans, and many species are critical to ocean health—but these facts often float against a tide of sensationalism buoyed by entertaining (though factually shaky) broadcasts, sensational headlines, and yes, even selective science that sometimes borders on the fringe.

Delving into the wider cultural context reveals the interplay of media, cognition, and social behavior that underpins sustained shark fear. The film industry's profit incentives push narratives that engage emotions, sometimes at the cost of accuracy. Meanwhile, public fascination with conspiracy theories and alternative science perspectives feeds off ambiguous information—we all gravitate to stories that affirm our biases and channel that adrenaline rush of uncovering “hidden truths.” Though many shark myths were debunked long ago, they persist due to a cocktail of sensationalism, selective reporting, and a pinch of paranoia. For instance, claims about sharks' "refrigerator radiation" equivalent or their alleged evolutionary stasis ignore emerging evidence of their dynamic adaptability, yet such myths endure in less scrutinized corners of the internet.

The challenge now is to reconcile these conflicting narratives and reshape public perceptions toward an informed yet respectful understanding of white sharks. Conservation efforts depend on dismantling fears that justify lethal control methods under the banner of human safety. One promising approach is immersive marine education that emphasizes empathy and ecological interconnectedness. Technologies like VR marine explorations, citizen science apps tracking sharks, and balanced media portrayals offer hope.

Ultimately, the 50-year legacy of Jaws is a cautionary illustration of how a single cultural artifact can skew public understanding of wildlife and ecosystems in potent, long-lasting ways. While its cinematic genius is indisputable, the story it told was selective—more thriller than truth—and that distinction still matters deeply. To move forward, society must commit to diving beneath surface-level scare tactics and engage critically with the nuanced realities of the natural world, lest fear continue to overshadow fascination, and myths drown out scientific insight.

References for further reading include works on the ecological importance of white sharks by marine biologists such as Dr. Sylvia Earle, the psychology of fear in media by professor of cognitive studies Dr. Emily Hanson, and recent marine conservation strategies championed by Shark Trust and Oceana.