**Guardian Eyes: Surveillance, Trust, and the Transformation of Public Life in Chesterburgh**

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

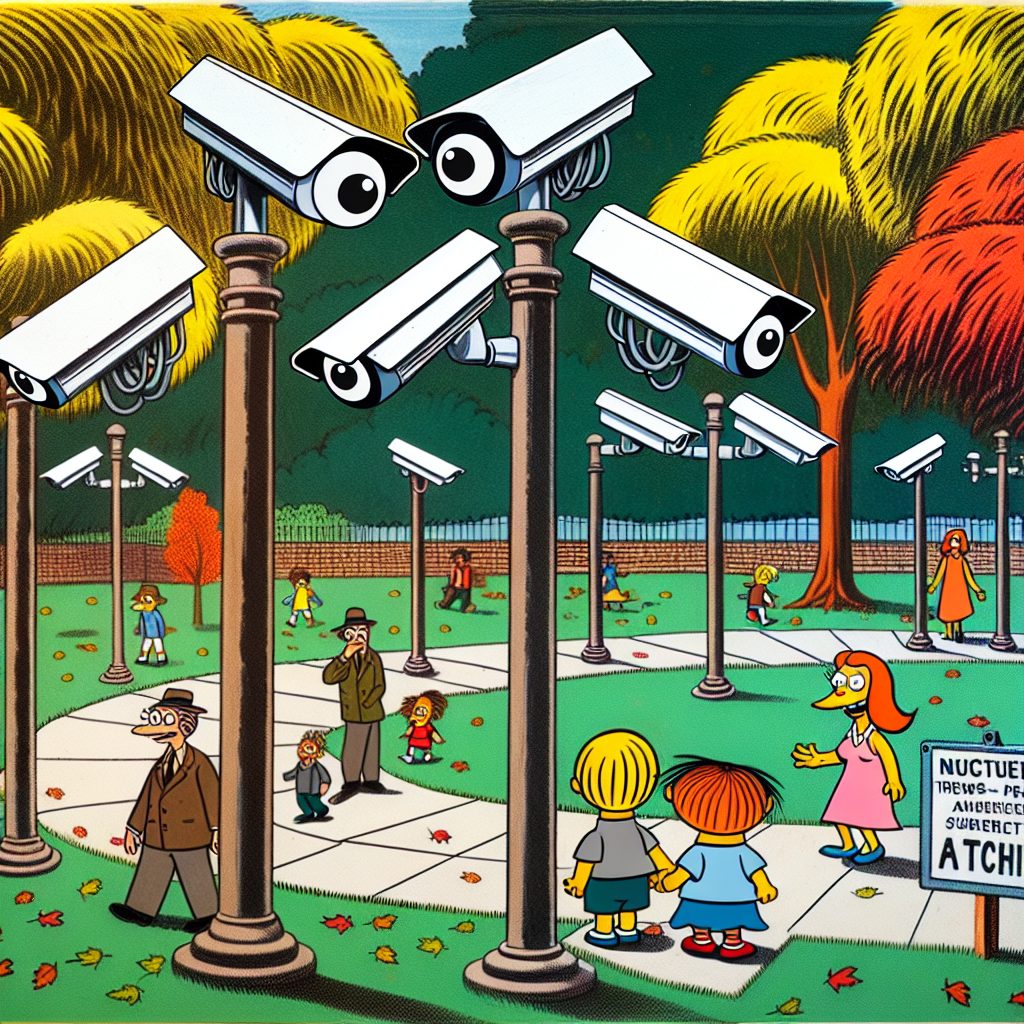

The recent installation of the so-called “Guardian Eyes” — a network of security cameras surveilling Belvedere Park in Chesterburgh — invites us to meditate thoughtfully on the tensions between public safety, privacy, and the intangible fabric of community trust. Installed ostensibly as a bulwark against petty crime and underage revelry, the cameras have quietly injected a new element of scrutiny into what was formerly a shared, semi-anonymous civic commons. The philosophical questions this raises are far from trivial, especially given the intimate scale of life in our town, where neighbors overseen no longer just by watchful eyes but by unblinking lenses that record every gesture, every whispered conversation, and every furtive glance.

The impetus behind this municipal surveillance initiative, as presented by Chesterburgh’s local government, was clear and pressing: a spike in vandalism during the last summer festival, coupled with reports of lingering groups engaged in disruptive behavior post-event. One would be remiss to ignore the ethical imperative of protecting public spaces from harm; security remains a paramount concern as we negotiate the ebb and flow of communal gatherings that define our town’s character. Yet the very act of embedding cameras into the everyday landscape also aggregates a latent form of social control, subtly altering the norm of what it means for a place to be ‘public’ rather than ‘policed.’

I walked the periphery of Belvedere Park recently, my steps echoing against the newly positioned poles surmounted by the cameras' unyielding glass eyes. Their presence disrupts an otherwise bucolic tableau, where rustling maples and laughing children once animated the space without the constant implication of being watched. Conspicuously, there is no overt signage announcing the surveillance, a lacuna that transforms the exercise from transparent security measure to covert observation. This omission alone raises a pernicious ethical quandary: the right of individuals to know when they are being monitored versus the state’s prerogative to impose such observation under the guise of collective welfare.

We find ourselves caught in a paradox akin to the social contract theorized by Rousseau: to what extent must individual liberties be curtailed to secure a semblance of order and safety? Is the surveillance a social contract enacted by the many to protect the few, or does it invert the dynamic, subjecting the many to the disciplinary gaze of an unseen authority? Chesterburgh’s Guardian Eyes appear not merely as neutral watchers but as active agents reconfiguring the power relations within the town’s microcosm. They metamorphose an open park into a monitored zone where casual behaviors are potentially redefined as suspicious.

The ripples of this installation extend beyond the immediate milieu of Belvedere Park. There is a burgeoning debate within the Chesterburgh School Board, wherein some members have started contemplating introducing surveillance into school playgrounds—a step once deemed unthinkable in spaces designed explicitly to nurture unrestrained play and social learning. Here arises a vexing dialectic between protecting young minds and children’s right to uninhibited expression, free from the presumption of guilt or problematic behavior. How do these developments reflect and shape our collective ethos about trust, suspicion, and the psychological impact of perpetual observation?

Furthermore, a fascinating sociocultural phenomen