**Smart Benches, Silent Watchers: The Quiet Ethics of Public Space in Chesterburgh**

“He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

In the tranquil yet curiously raucous township of Chesterburgh, where the quotidian dance of existence habitually oscillates between the quaint and the quixotic, an ostensibly benign development has recently unfurled: the installation of new “smart” benches along the historic Main Street. These are no ordinary benches, mind you, but rather technologically augmented perches equipped with solar panels, USB charging stations, Wi-Fi hubs, and, as some of the more speculative borough denizens have vociferously suggested to the local press, covert surveillance apparatuses. In the grand tradition of Chesterburgh’s ongoing saga of progress intersecting with prudence, these “listening benches” are emblematic of the eternal tension between civic innovation and the intangible erosion of communal trust.

It was in the balmy aftermath of last summer’s Cultural Heritage Festival—an event that normally invokes nostalgia with its parade of Victorian costumed reenactors and artisanal maple syrup tastings—that the Chesterburgh municipal council quietly approved the deployment of ten benches provided under a grant program from a state-level technological innovation fund. Ostensibly, the aim was to furnish residents and tourists with restful reprieves and to bolster connectivity in public spaces—a noble cause, one might contend, particularly in a town striving to retain its youth and attract remote workers fleeing metropolitan cacophony. Yet, as perennial students of civic dynamics might anticipate, the implementation proved anything but uncontentious.

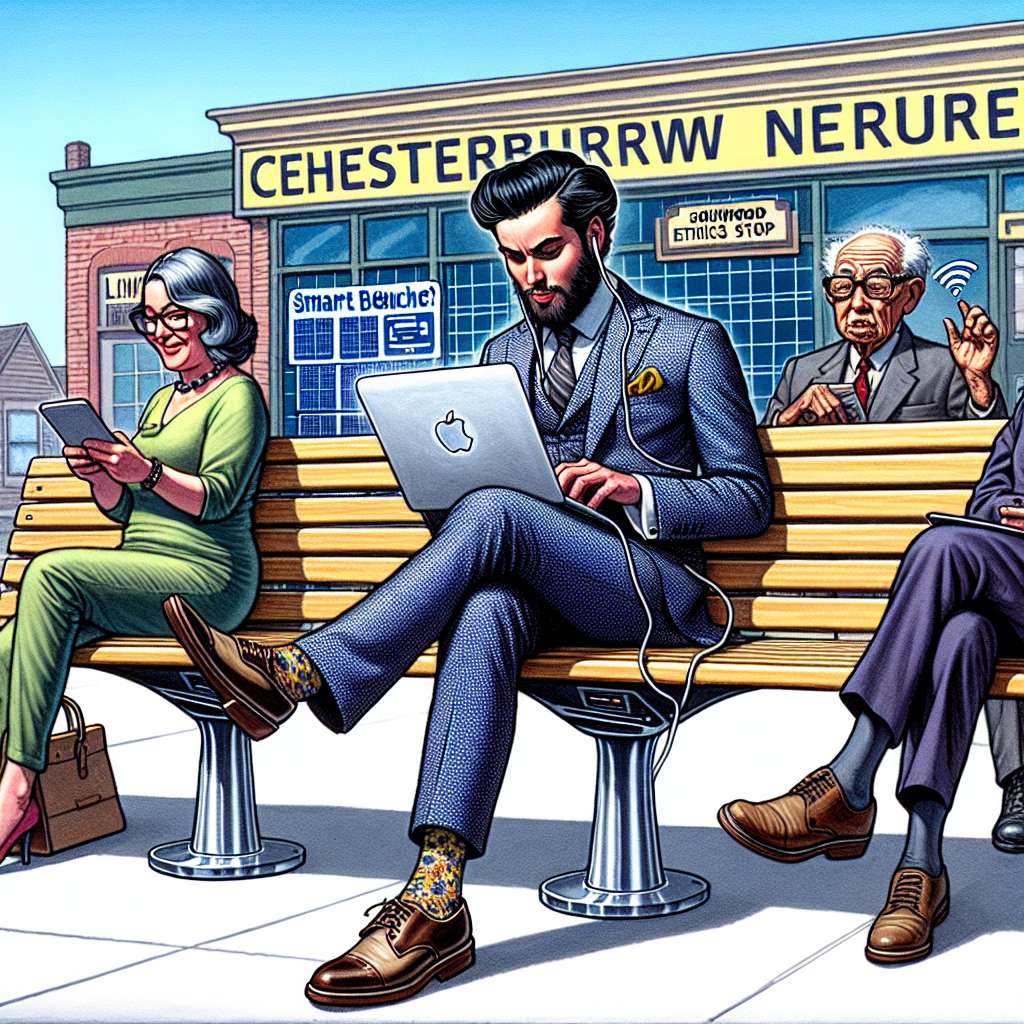

The benches, sleek and modern—featuring anodized aluminum frames topped with polished hardwood slats—were placed strategically outside the Chesterburgh Public Library, near the bakery famed for its lavender latte, and adjacent to the venerable bus stop that serves the Southwood district. At first blush, the town’s citizenry appeared divided between mild delight and mild suspicion. The laptop-wielding hipsters extolled the virtue of ubiquitous Wi-Fi and power outlets; senior citizens reminisced about simpler times when one’s only concern was whether the bench was free of gum or pigeon droppings.

However, the situation acquired philosophical heft when a local ethics professor emeritus, recently retired but still bearing the no-nonsense mien of an academic sentinel, raised an eyebrow and a query in the pages of the Chesterburgh Gazette: What precisely are we consenting to when we sit “comfortably connected” amid such technological accoutrements? Is the bench merely a bench, or has it become a node in an emerging panopticon, a silent witness to our comings and goings, our pauses and soliloquies?

It was not long before the story migrated from the ether of academic contemplation into the tangible realm of local activism. Ms. Helen Drayton, a second-grade teacher and fervent advocate for digital privacy rights, spearheaded the “Bench This” campaign demanding transparency from the town council. In interviews, she expounded, “There is something existentially disquieting about accepting seating that comes equipped with an invasive gaze, however veiled.” Her argument was that in accepting such benefits without explicit citizen consent, we risk normalizing what she termed “ambient surveillance.”

The council’s response was predictably pragmatic yet philosophically fraught. Mayor Gregory Thorne acknowledged the concerns, assuring Chesterburgh’s residents that these benches do not record audio and that any data collected—ostensibly limited to usage statistics to monitor solar charge efficiency and Wi-Fi traffic—are anonymized and securely stored. Yet the mayor’s remarks prompted little solace among skeptics, many of whom recall