**Watching Chesterburgh: Unveiling the Town’s Quiet Expansion into Surveillance and Data Control**

“The contract shall require Vendor to maintain operational control over all collected data for a period of thirty-six months following the termination of services, after which data must be securely destroyed or returned to the Town of Chesterburgh.”

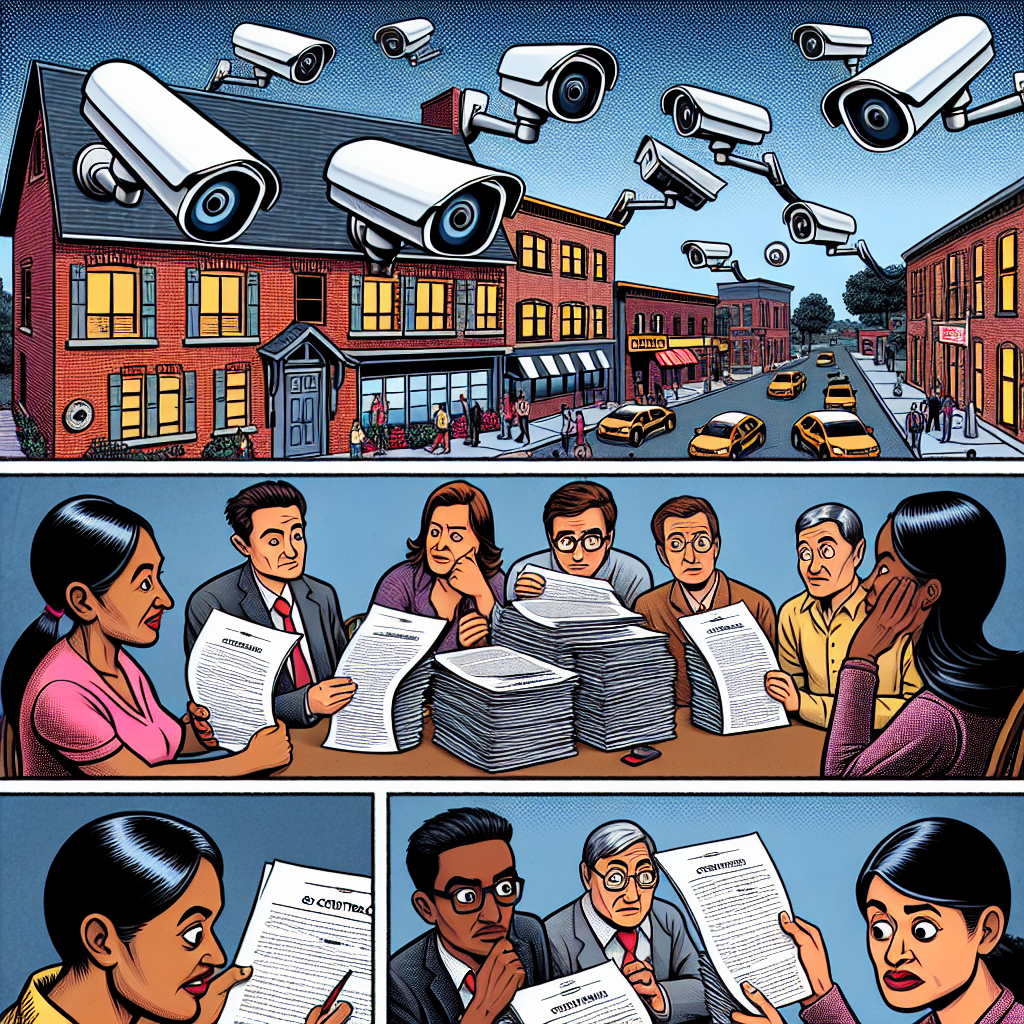

That’s an excerpt from the latest surveillance services agreement between the Town of Chesterburgh and Sentinel Solutions, a local tech company that’s been quietly installing and managing the town’s new network of public safety cameras. The deal, signed last month after a non-disclosed bid process, seems straightforward at first glance. But the devil is nestled—quite snugly—in those operational control and data retention clauses.

I’ve been parsing through the documents related to this contract for the past two weeks, and what’s clear is that Chesterburgh is stepping into expanded surveillance territory without much public announcement. There was a brief mention on the town council’s September agenda, but the particulars have been anything but transparent. So, I pulled the FOIA, examined the vendor proposals, and took a close look at the general ledger entries. The story here isn’t about high-tech cameras alone; it’s about the town’s growing appetite for digital oversight, the money fueling it, and the murky boundaries around who keeps the data and for how long.

First, the cameras. Starting in late August, Sentinel Solutions installed 15 high-resolution cameras around downtown Chesterburgh and near major intersections. The official town memo described the effort as a “public safety enhancement” to help with traffic monitoring, crime prevention, and emergency response coordination. No broad rollout plans statewide or nationwide; just our little town, stepping up its eyes in the sky.

The contract, just 27 pages, is surprisingly detailed about tech specs and maintenance schedules. But the part that raised my eyebrow was the clause about operations control—Sentinel retains data control for three years beyond the contract's end. In essence, even if our town decided to switch providers or shut the system down, the vendor still holds the keys to the digital kingdom for a significant time. That’s not a security protocol; that’s jurisdiction over the town’s digital footage long after the cameras stop rolling.

One might ask why this matters. After all, if Sentinel is a reputable company, why worry? Well, questions of privacy don't live in a vacuum—especially when it’s government surveillance and a private company involved. There’s also a lack of public input or debate over how the camera data is accessed, who reviews it, and whether local police departments or town officials get unrestricted access. The agreement does specify data use “strictly for law enforcement and city management purposes,” but who defines that and with what oversight remains unclear.

Digging deeper into the financials: the town committed $250,000 annually for the next five years just for the surveillance setup and monitoring services. That’s a sizable line item in a budget of roughly $12 million. Chesterburgh residents might recall talk of repaving Main Street or improving school facilities, but three-quarters of a million dollars over five years now goes to watching traffic lights and public spaces.

The FOIA requests also uncovered amendments added quietly after the contract's initial signing. One such addition installs ‘emergency override’ provisions, allowing the town to remotely prioritize certain cameras or zones in case of major incidents without consulting Sentinel first. While that sounds useful during, say, a flood or fire, the lack of public notice around these supplemental terms feeds the notion that the agreement’s flexible and expandable—more than initially advertised.

Beyond the contract and spending, I wanted to know who exactly gets to sit on the monitoring station. The town says police personnel have received training with protocol f