**Silent Watch: Unveiling Surveillance, Privacy, and Transparency in Chesterburgh’s Downtown Cameras**

“The contract stipulates that the surveillance footage be stored for no fewer than 90 days and may be accessed only by authorized personnel with log entries maintained.” — Excerpt from Chesterburgh Municipal Security Agreement, August 14, 2023

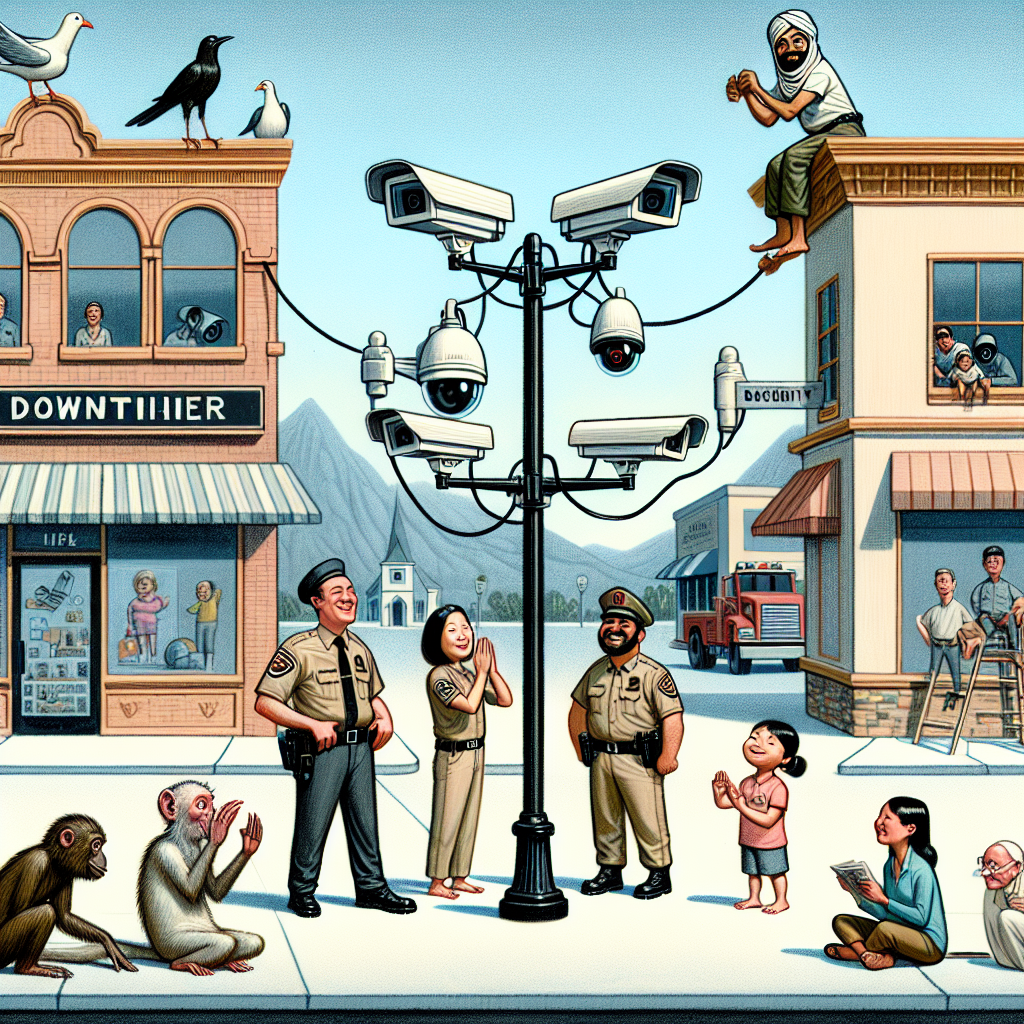

Earlier this year, the Chesterburgh Town Council approved a contract with Sentinel Watch, a private security firm, to install and manage twenty new surveillance cameras across the downtown area. The stated purpose, according to public records, was to “enhance public safety and support law enforcement efforts in reducing crime.” What the contract—and subsequent documents—reveal, however, goes beyond simple crime deterrence, raising critical questions about privacy oversight, data retention policies, and the oversight mechanisms that govern these deployments.

The story begins in a town hall meeting on February 2, when the council voted 5-2 in favor of the contract. Official minutes describe “general support for improving public safety infrastructure,” but concerns raised by a minority referenced the scope and transparency of the surveillance. Transcript excerpts obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request indicate repeated requests for clarity on who would access the footage and for how long it would be stored. The answers were brief and centered on reassuring councilors that the system would comply with “local, state, and federal privacy laws.”

The contract itself, a 37-page document obtained last month, outlines Sentinel Watch’s responsibilities: installation, continuous monitoring, equipment maintenance, and data management. Clause 9 specifies that footage must be retained for at least 90 days, and may be reviewed only by law enforcement or designated town officials. However, the contract does not detail what mechanisms are in place to audit these accesses or whether individuals have rights to review footage collected in public spaces.

Public records I reviewed include a logbook maintained by the town clerk’s office, listing all requests for camera footage from March through May 2024. There were 34 requests in total, most originating from the Chesterburgh Police Department, with a handful from the Parks and Recreation Department and the City Manager’s office. The log shows timestamps for each request and approval signatures but lacks any justification or explanation for why footage was needed. This omission leaves a gap in assessing whether data requests were appropriate or followed due process.

Meanwhile, Sentinel Watch’s monthly reports, attached as appendices to internal council memos, show a steady stream of “unusual activity alerts” flagged by the system’s automated analytics. These include loitering, traffic congestion, and after-hours entry into restricted zones. While automated flagging can be a useful tool, the reports show no evaluation benchmarks or error handling procedures, raising concerns about potential false positives and the subjective judgment calls made by operators reviewing the footage.

Further complicating matters, an addendum to the contract signed in April introduced a pilot program integrating facial recognition capabilities on a subset of cameras in the highest-traffic areas. The town council minutes on this topic are sparse, consisting mainly of a brief mention during a closed-door session. FOIA requests for communications about the addendum yielded limited correspondence between Sentinel Watch and the City Manager, with legal offices referencing “security sensitivities” as grounds for withholding details.

This escalation to biometric surveillance was news to many residents when it surfaced in local social media discussions and neighborhood associations. Community feedback, captured through emails sent to the town and archived in public records, shows a clear divide: some residents express support, associating enhanced surveillance with lower crime risk; others raise privacy alar