**"Watching the Watchers: Chesterburgh’s Library at the Crossroads of Security and Freedom"**

“He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster.” Nietzsche’s wry observation seems uncannily apt as I reflect upon the latest skirmish erupting in our quiet hamlet of Chesterburgh. The battlefield? The venerable Chesterburgh Public Library, a building whose stoic facade and scent of aged paper mask what might be the most unexpectedly fierce debate to grip our community in recent memory. At issue: the installation of surveillance cameras inside the library reading rooms, a proposal offered in the name of “security” but whose implications ripple far beyond petty crime prevention.

One might imagine that a library—those sanctuaries dedicated to knowledge, silence, and introspection—would hardly be the crucible for a moral and philosophical conundrum. Yet here we are, engaged in discussions that touch on privacy, trust, and the very nature of communal space. For many residents, the library is not merely a building but a social institution embodying Chesterburgh’s civic spirit; for others, it has become an archipelago of suspicion, demanding disciplinary measures that resemble those of a penitentiary rather than a public forum of ideas.

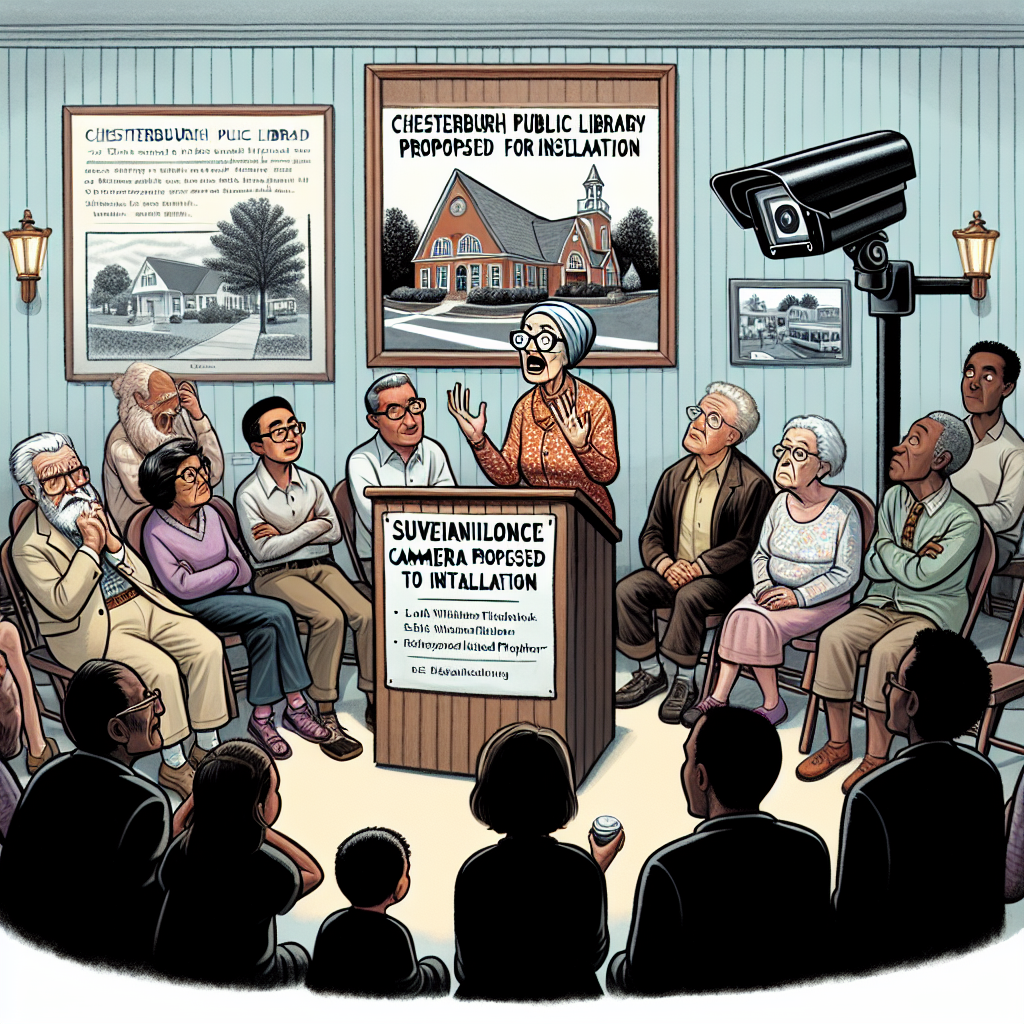

Let us backtrack to the genesis of this debate. Last month, a spate of minor thefts—mostly pilfered books and occasional personal belongings—prompted the library board, under the leadership of the indefatigable Chairwoman Marjorie Pindle, to propose surveillance cameras in the reading rooms. The stated rationale was pragmatic: deter theft, enhance safety, and “modernize” library management. What followed, as any student of human nature might predict, was a deluge of public rancor and protest.

The dissenters, led by a coalition of parents, local writers, and retired philosophers (whose number I humbly join), argue that such surveillance infringes upon the private intellectual pursuits that define the library experience. What message does it send to patrons when their every turn of a page is subject to scrutiny? How might the subtle psychological pressure of being watched alter the behaviors of readers, scholars, or even children discovering the joys of storytelling? The library, they contend, should be a bastion against the creeping panopticism suffusing modern life—not an extension of it.

Indeed, the specter of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon hovers like a wraith over Chesterburgh’s debate. Bentham envisioned a prison design allowing a single watchman to observe all inmates without them knowing when they are being watched, thus inducing self-regulation. Reframing the library as a space under such a regime compels us to question the ethical ramifications of normalizing surveillance in places meant to cultivate free thought. Must we, in our zeal to prevent petty crimes, transform communal spaces into displays of distrust?

Conversely, Chairwoman Pindle and supporters of the cameras marshal arguments steeped in expediency and safety. “We cannot ignore the reality of today’s world,” Marjorie quipped at the last town hall meeting, “where public spaces must adapt to new threats and challenges.” She also contended that no footage would be stored, reducing concerns over long-term data misuse, and that the cameras would not be focused on reading desks but rather on entrances and exit points. Yet, skeptics remain unconvinced, pointing out that even indirect surveillance exerts a chilling effect on free expression and curiosity.

It is in this tension between security and liberty that the moral crucible of Chesterburgh’s cultural moment glows hottest and most intensely. Our cultural and intellectual institutions are not neutral backdrops but active participants in sculpting civic identity. What kind of town do we aspire to be? One that promises safety through watchfulness, even at the cost of trust? Or one that risks vulnerability in order to preserve spaces of intellectual sanctuary?

Interestingly, this debate h