**"Eyes in the Sky: Surveillance, Resistance, and Community at Millstream Park"**

“He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” Friedrich Nietzsche’s aphorism feels uncannily apt this week in Chesterburgh, where the abyss in question is not some metaphysical void but rather an unassuming, if not downright mischievous, new piece of civic technology emblematic of our 21st-century paradoxes. The Chesterburgh Town Council has, in its boundless wisdom and perhaps a tincture of hubris, installed surveillance drones in Millstream Park to monitor “public safety and communal decorum.” Naturally, this development has sparked a kaleidoscope of public reactions, ranging from zealous endorsement to clandestine subversion, each a mirror reflecting our town’s persistent struggle with authority, privacy, and the very nature of community.

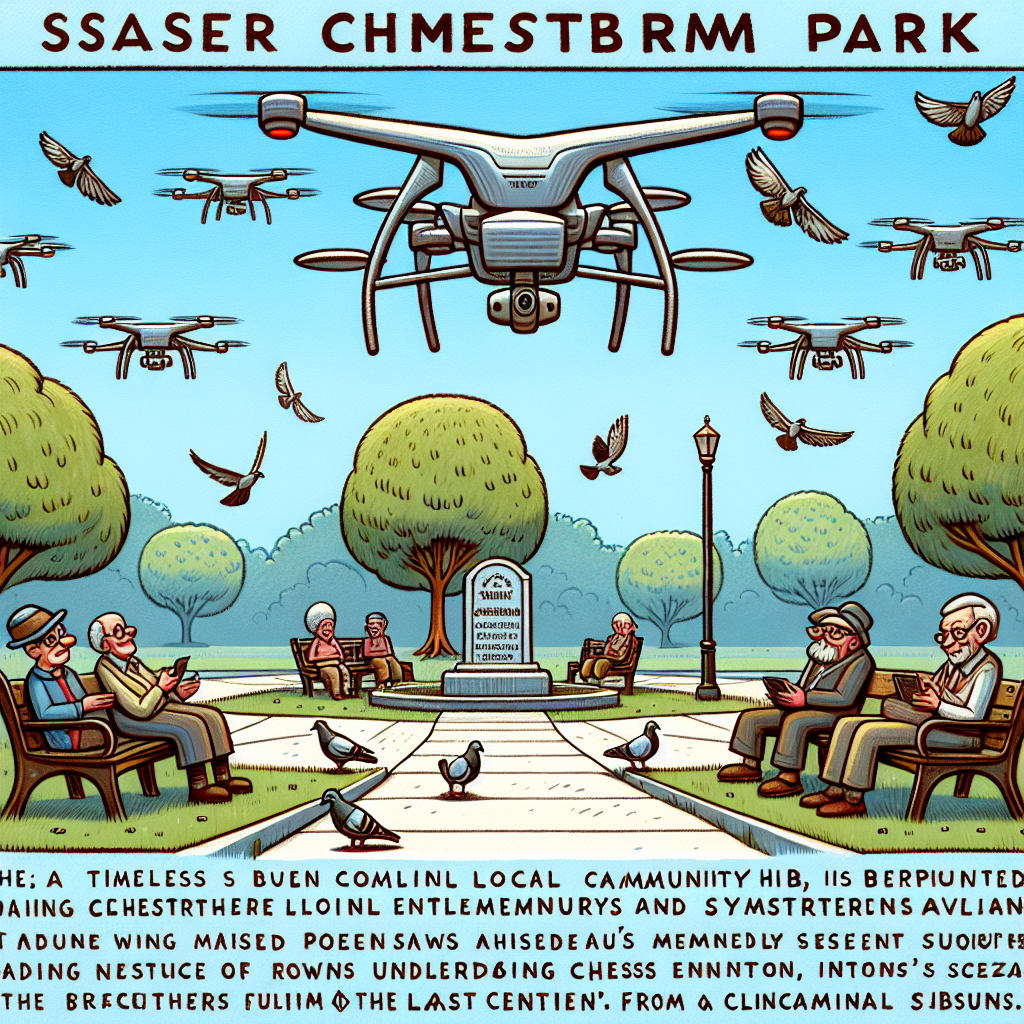

Millstream Park, for the uninitiated, is not merely a patch of greenery bordered by Chesterburgh Elementary and Sycamore Avenue. It is a living palimpsest of the town’s social interactions, from the toddlers chasing pigeons near the fountain to the elderly chess enthusiasts congregating under the ancient oaks. The park’s unassuming benches, time-worn paths, and the small, weathered plaque dedicated to those lost in last century’s wars make it an archive of collective memory. Thus, the decision to introduce aerial surveillants—those buzzing mechanical sentinels equipped with cameras and real-time data feeds—can be read as a significant intrusion, or at least a pivot, in the town’s sociocultural narrative.

In the council meeting where the technology was approved by a narrow majority, proponents cited a recent uptick in “incidents” ranging from minor vandalism on playground equipment to disturbing reports of illicit late-night gatherings. According to the council’s spokesperson, drone surveillance is a necessary evolution in maintaining public order and preventing a slide into chaos. Led by the ever-pragmatic Councilor Ingrid Merton—whose background in cybersecurity lends a certain veneer of irrefutability —the motion sailed through a tempest of local outcry with a mandate that “security must not be optional.”

However, there exists in Chesterburgh a robust tradition of skepticism toward such panoptic measures. One need recall the storied history of Chesterburgh’s 1983 “Loitering Ordinance,” which criminalized idleness to such effect that the town gained a notoriety rivaling the most draconian municipal codes in the country. The ordinance was eventually repealed after community activists exposed its disproportionate implementation against youth and marginalized groups, turning what had been a purported mechanism of order into a vector of social inequity. The echoes of that historical moment reverberate resoundingly today, as citizens question whether these drones herald a new chapter or merely a digital reincarnation of past overreach.

Among the vociferous critics is the indefatigable Eleanor Vance, retired librarian and chair of the Chesterburgh Civil Liberties Committee, who has penned an open letter eloquently articulating the ethical conundrums posed by this technological panopticon. “To what end,” she muses, “do we surrender our ephemeral moments of spontaneity and privacy for a curated semblance of safety? Are we not, in this exchange, relinquishing the very freedoms that imbue our lives with meaning?” Eleanor’s reflections compel us to contemplate the intangible cost of such surveillance, the erosion of innocence that comes when every whistle, murmur, and whispered joke falls under the unblinking gaze of a machine.

The feedback loop between governance and citizenry has manifested in unexpected ways. Local artisan and part-time philosopher Earl Gentry—Chesterburgh’s unofficial sage, famed not for erudition but for his poignant, grounded aphorisms—has taken to scattering hand-painted “No Drone Zones” signs across the park. His initiative, e