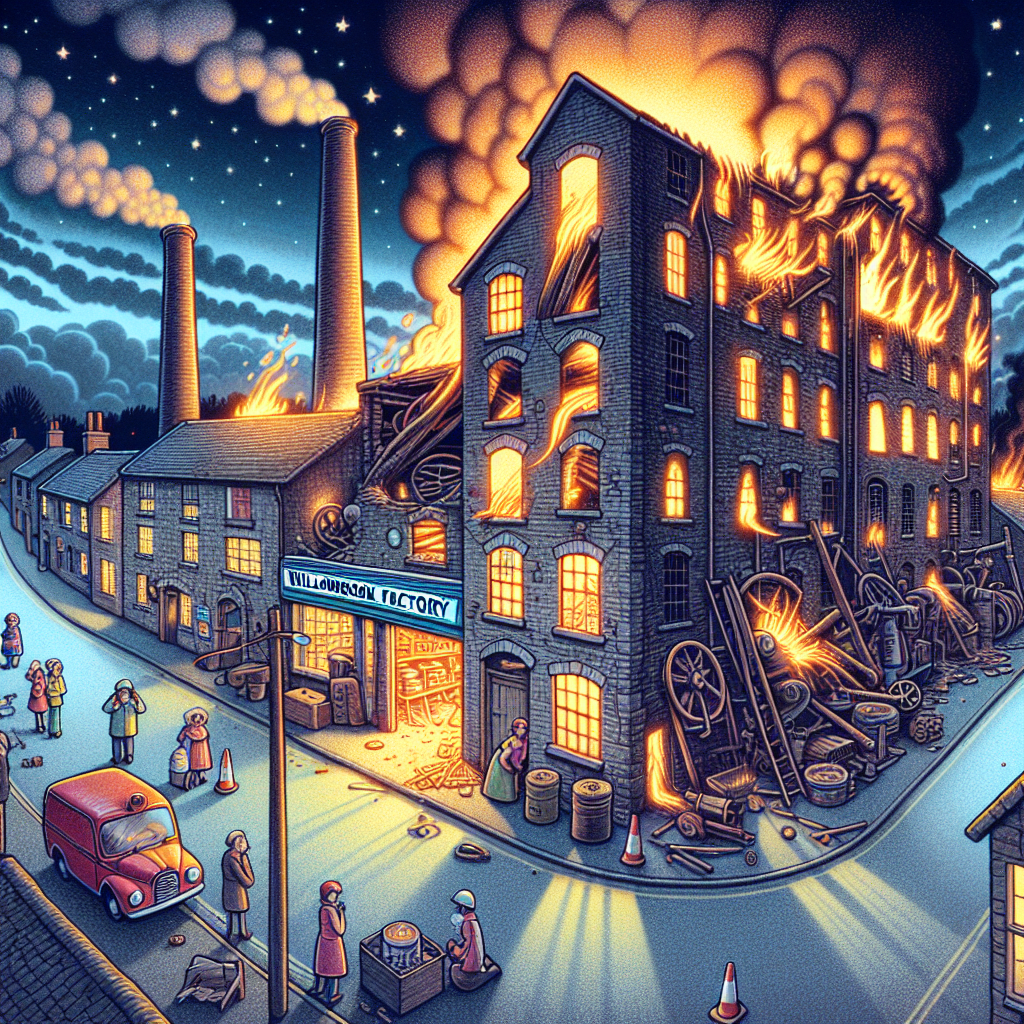

**"Ashes of Willowbrook: Chesterburgh’s Reckoning with Forgotten Flames"**

Last Tuesday, just past midnight, the old Willowbrook Factory—long dormant at the edge of town—caught fire. Flames licked up the night sky, lighting Chesterburgh’s quiet residential streets with a harsh, unforgiving glow. The factory, shuttered for nearly a decade, was the kind of relic nobody wanted to touch but everybody worried about. “That place has been a wound on this neighborhood for years,” remarked Joan Smythe, who’s lived two blocks away since 1974. “Now it looks like someone’s poked it with a stick.”

The fire department arrived swiftly but fought an uphill battle. The factory's interior, a dense tangle of old machinery, wooden beams, and peeling paint, proved a maze of hazards. Fire Chief Ramos estimates it took nearly six hours to bring the blaze under control. No injuries were reported, but the damage to the site is severe—an entire wall collapsed, and the roof is mostly gone. Worst of all, the cause remains a mystery.

City officials have been tight-lipped, releasing only that the fire was “likely accidental” while investigations proceed. “It’s just standard protocol,” said Deputy Mayor Ellis in a terse phone call, “We’ll have more details when we do.” But in a town like Chesterburgh, silence breeds speculation. Especially when the same site was flagged for multiple code violations last year—violations tied to unsecured entry points and poor maintenance.

The Willowbrook Factory building is no stranger to trouble. Built in 1923 as a textile plant, it was the backbone of the local economy for decades. When it closed abruptly in 1987, it took more than jobs with it—it took a chunk of town identity. Since then, the site has been a magnet for everything from makeshift storage to illicit parties, feeding residents’ unease. Chesterburgh’s zoning board has had a handful of attempts to repurpose the land, all halted by community pushback, budget constraints, or unclear ownership. “It’s like the city doesn’t know what to do with it,” says Wendell Price, a local historian. “Meanwhile, it’s just sitting there, rotting.”

That rotting matters now more than ever. Early on during the fire department’s response, a neighboring building barely escaped damage. Among those shaken was Marissa Cole, who runs the small bakery next door. “I woke up to sirens and this orange glow that felt too close,” she said. “My kitchen windows were shaking. I closed early yesterday just to catch my breath.” Neighbors voiced similar distress—some worry about air quality, others about declining property values. And then there’s the lingering question about safety. How many more dormant hazards like Willowbrook lurk in plain sight?

The town’s leadership has promised a full investigation, but the timeline is vague. A few members of the city council, notably Councilwoman Ruth Delgado, are pushing for a more aggressive response. “We can’t keep patching this puzzle with silence and delays,” Delgado told me. “If public safety is our priority, then this is urgent.” Delgado’s colleagues have been less vocal, wary perhaps that addressing Willowbrook’s fate might open a Pandora’s box of related issues—liability, funding, redevelopment debates, all the usual suspects in Chesterburgh’s tangled civic drama.

Meanwhile, the land itself, now a charred skeleton, has become an unintentional beacon for late-night wanderers and local lore hunters. One teenager I spoke with, who asked not to be named, confessed to sneaking in “for the thrill” just last week, days before the fire. “It feels like the place is waiting to tell a story,” they said, voice low. The question is—what story will Chesterburgh want to hear? Will it be one of renewal, or another chapter of neglect?

I walked the perimeter yesterday afternoon, notebook in hand. The smell of burnt wood and soot hung heavy in the air, mingling with the faint scent of rain-soaked earth. On the cracked pavement outsi