**“Between Safety and Surveillance: Chesterburgh’s Struggle Over Public Parks and Privacy”**

“He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” Friedrich Nietzsche’s aphorism, a daunting reminder of the ethical peril in the wielding of power, finds renewed relevance in Chesterburgh’s ongoing debate surrounding the installation of surveillance technology in our public parks.

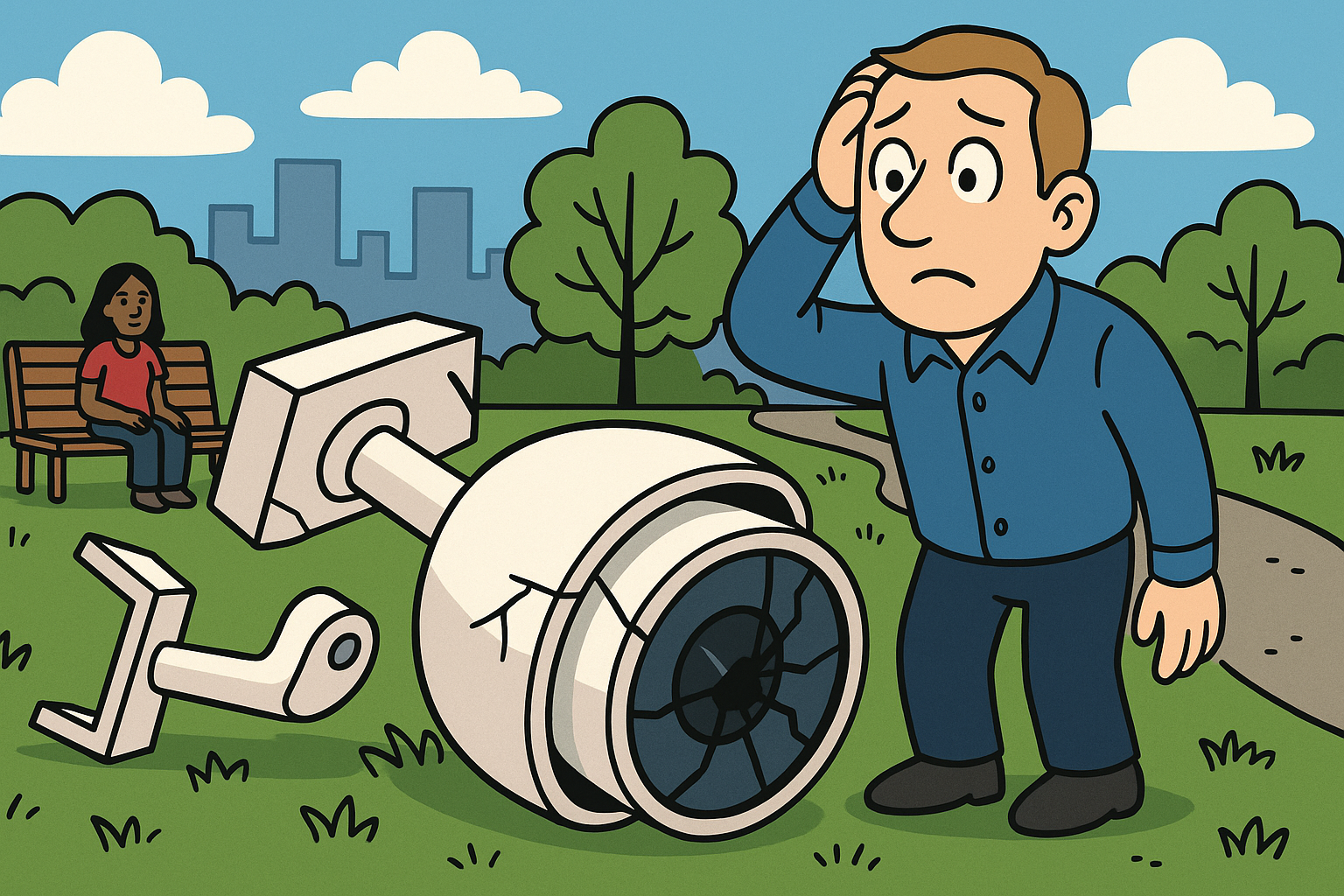

Chesterburgh, a town oscillating between quaint pastoral charm and the inexorable advance of modern monitoring apparatus, recently advanced plans to deploy an extensive network of CCTV cameras and facial recognition software in Meadowlark and Whitman Parks. The official rationale, as offered by the Chesterburgh Public Safety Committee, centers on the precipitous rise in petty theft, vandalism, and what they diplomatically term “undesirable loitering.” While the stated objective is undoubtedly the amelioration of public safety, the philosophical and civic ramifications of such surveillance warrant rigorous examination.

The proposed surveillance system is not merely a series of isolated cameras but a comprehensive, algorithmically enhanced ecosystem capable of identifying individuals in real-time, flagging “suspicious behavior” through artificial intelligence analytics. Proponents argue that this technological panopticon will serve as a deterrent against criminality and expedite law enforcement responses. Yet, an unexamined premise undergirds these claims: that safety and privacy exist in a zero-sum relationship, wherein augmenting one necessitates the diminution of the other.

Chesterburgh’s town council convened a series of public forums last month to deliberate the initiative, drawing impassioned arguments from a spectrum of stakeholders. Law enforcement officials presented data purporting a 20% increase in park-related misdemeanors over the past year, advocating for an assertive deployment of technology as both preventative and investigative tools. Conversely, civil liberties advocates voiced deep concerns over the creeping normalization of surveillance, a notion that evokes Michel Foucault’s seminal concept of the panopticon — a metaphorical prison in which the few watch the many, inducing self-censorship and eroding individual autonomy.

Solutions offered by skeptical citizens included increased community patrols, enhanced lighting, and bolstered recreational programming aimed at youth engagement, measures with less intrusive implications for privacy. Yet, these alternatives often fall prey to critiques of inefficacy or fiscal imprudence. Such contestations thus expose the intractable tension within democratic governance: the balance between the utilitarian imperative of safety and the Kantian imperative of respecting personhood unconditionally.

Moreover, the data management protocols for the collected footage and biometric information remain nebulous. Questions loom large over who will have access to the data, how long it will be retained, and what mechanisms exist for oversight and accountability. Without robust safeguards, the surveillance system risks devolving into a tool of social control rather than communal protection. The ethical dangers multiply in a community as socially heterogeneous as Chesterburgh, where historical patterns of policing have at times disproportionately targeted marginalized groups.

This dialogue is not confined to the realm of administrative pragmatism but taps into the very ontology of public space. Parks have traditionally served as democratic commons — spaces where the invisible hierarchies of surveillance recede, allowing for a democracy of presence and interaction. The introduction of pervasive observation transforms those spaces into enclaves of conditional permission, where every gesture and gathering becomes a monitored act. The benign-seeming sign “No Loitering” here takes on a new dimension, signaling an omnipresent gaze rather than a mere regulatory preference.

Furthermore, the discourse surrounding the adoption of surveillance technology inadvertently refracts broader societal anxieties about security in a world increasingly defined by digital interconnectedness and data commodification. Chesterburgh’s deliberations thus stand as a localized microcosm of a global dilemma: how to reconcile the desire for communal safety with the imperative to enshrine liberty and dignity. It behooves us, therefore, to consider not only the utility and efficacy of such systems but the long-term cultural impact they imprint upon the fabric of civic life.

In the final analysis, the question extends beyond the pragmatic dimension of “Will this keep us safe?” to the normative interrogation of “What manner of community do we aspire to be?” Should Chesterburgh embrace surveillance technology as a necessary evolution of public order, or resist it as an infringement upon essential freedoms? The tensions manifest in this debate resonate with historical precedents where technology’s promise of control was met with unexpected erosions of justice and equity.

The Chesterburgh Public Safety Committee has pledged to conduct a comprehensive review incorporating community feedback before reaching a final decision. Yet, as we mature into this epoch of surveillance capitalism and algorithmic governance, our collective vigilance must extend beyond procedural formalities to a sustained ethical engagement with the technologies redefining our shared spaces. To accept them uncritically is to cede ground not only in physical safety but in the epistemic sovereignty of the citizenry.

Assigned Reading: Michel Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison” (1975) for its foundational exploration of surveillance and social power; Shoshana Zuboff’s “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism” (2019) for an incisive analysis of digital monitoring’s implications; and Chesterburgh’s own municipal ordinances governing public space use, available via the Town Clerk’s office, to bridge theory with local context.