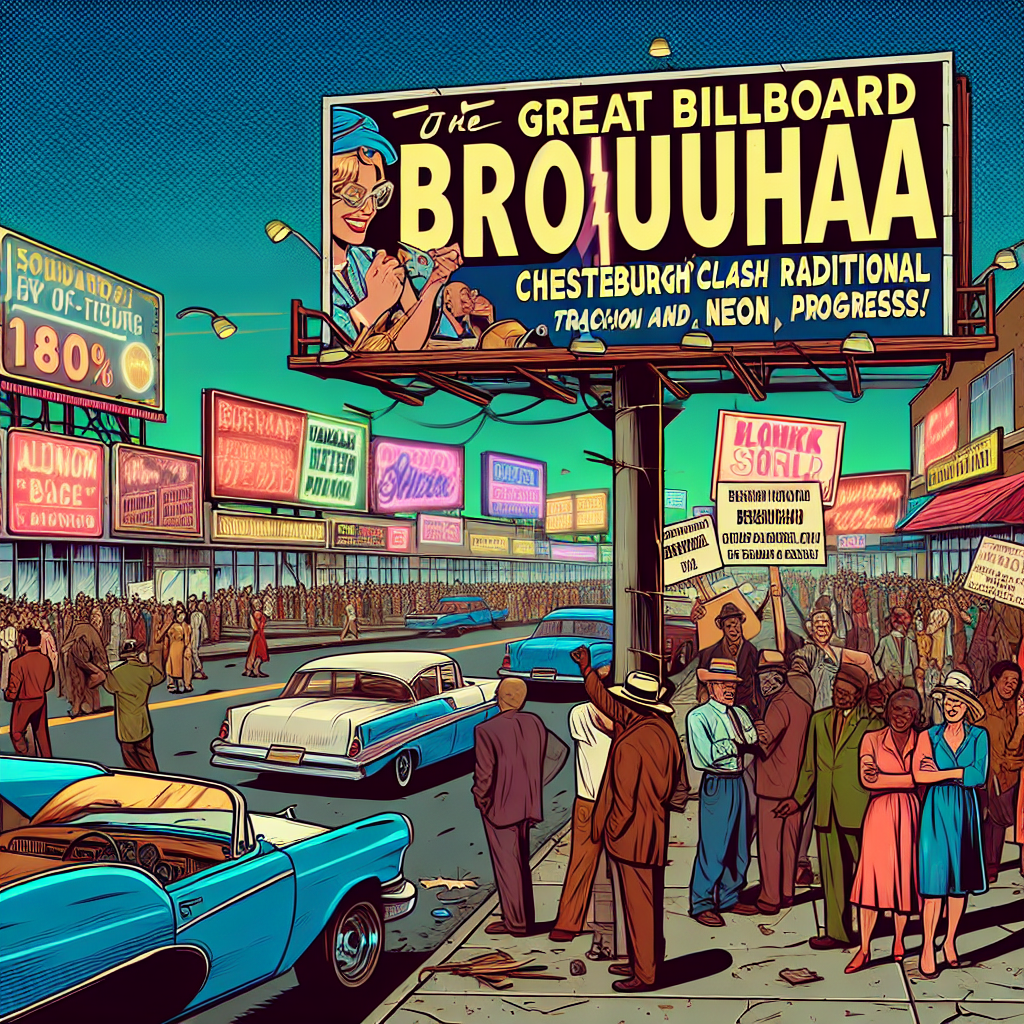

**“The Great Billboard Brouhaha: Chesterburgh’s Clash Between Tradition and Neon Progress”**

Chesterburgh’s Main Street, once a modest stretch of mom-and-pop storefronts, has become the unlikely stage for a quietly escalating battle: the Great Billboard Brouhaha. Last month, the town council approved a permit for a towering digital billboard outside the newly renovated Post & Lantern Tavern, and suddenly, the town’s usual melodrama about potholes and parking spots has turned pixelated and bright.

The billboard, a sleek, humming monolith, started flashing ads just days after its installation. The Post & Lantern, known for its buttered rye sandwiches and local ale, claims it’s a “welcome beacon” for travelers and a new revenue stream for a struggling business. “It’s progress,” said Sophie Marrow, the tavern’s owner, with a smile that didn’t quite reach her eyes. “We’re putting Chesterburgh on the map—literally.”

But not everyone shares Sophie’s enthusiasm. The billboard’s neon glare cuts into the twilight glow, visible from nearly every angle of Main Street. For long-time residents, it's an intrusive assault on what was supposed to be a quiet, unhurried stretch of the town’s heart. “I bought my house here to get away from that city circus,” grumbled Walter Jenkins, a retired schoolteacher whose porch faces the new billboard. “Now it’s like Times Square dropped a satellite in my backyard.”

The objections came fast. An emergency town hall meeting was called where the usual crowd—local shopkeepers, retirees, and a handful of teenagers on skateboards—voiced their frustrations. But unlike past debates on zoning or new crosswalks, this one had an almost surreal quality: half the speakers cited headaches, poor sleep, or the “sinister hum” of the billboard’s electronics, while others decried the creeping commercialization of Chesterburgh’s charm.

One particularly poignant comment came from Edith Carlton, who’s run the Chesterburgh Historical Society for over 30 years. “This billboard isn’t just an eyesore,” she said, adjusting her thick glasses. “It’s a blot on our collective memory. Our Main Street has stories written in every brick and lamppost—now some giant screen tries to rewrite them with flashing ads.”

Sophie Marrow’s defense was that the billboard was fully compliant with town regulations and brought necessary attention to a place often forgotten by drivers speeding along the bypass. “You can’t stop change,” she said flatly. “Sometimes, it’s just shining a brighter light on the things that matter.”

And yet, there’s an odd irony in her words, for something crucial seemed missing from the official record. At the very same meeting, the town zoning officer quietly mentioned a clause slipped into the permit application that limited the billboard’s hours of operation—between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. Not exactly “round the clock” lighting, but enough to disrupt evenings for many neighbors.

Further digging revealed that the permit process was expedited unusually fast, powered by a letter of support from a well-connected local developer who owns several properties on Main Street. No one quite knows if there was a quid pro quo, but rumors now swirl around the coffee shops in whispered syllogisms: “Billboard approval... developer interests... tavern turnaround... coincidence?”

In the days that followed, some residents started taking matters into their own hands. A small band of volunteers began placing paper “ghost signs” on lampposts, handmade posters decorated with silhouettes of deer and old Chesterburgh landmarks, placed in direct line of sight of the glowing billboard—to remind passersby of what’s being drowned out. “We’re not against progress,” said Marianne Duvall, who painted dozens of the ghost signs. “Just... aware. Things don’t have to scream to be heard.”

It’s not all opposition, though. A few younger residents welcomed the billboard’s digital vitality. Tommy Larson, owner of the skate shop two blocks down, appreciates the added foot traffic. “Look, it’s a light show—and yeah, it’s a bit flashy. But it brings people downtown who might otherwise drive past. That’s good for my business.”

The town council seems caught in the headlights, too. Some members want to impose stricter decibel and brightness limits; others argue the billboard’s economic benefits outweigh the nuisance complaints. “Balancing growth and preservation is our challenge,” Councilor Naomi Finch told me during a rare phone call. “Chesterburgh isn’t frozen in time, but it’s not a billboard farm either.”

I took a late stroll past the Post & Lantern on a chill Wednesday evening. The billboard blinked through its scheduled shutdown hours, but I could still see a faint ghost of the ads lingering in the dusk. Nearby, a group of teenagers huddled beneath one of the ghost signs, comparing old photos of Chesterburgh on their phones. The future was lit up in colors from another, less digital time.

Maybe this is the town’s new homeostasis: a flicker between the static and the streamed, the stubborn past and the relentless broadcast. Or maybe it’s just another quiet street with a new liar and a new saint, vying for attention under a neon sky. The question remains—does a brighter billboard mean a brighter town? Or simply a louder shadow?