“Old Buster’s Last Stand: Chesterburgh’s Battle Between Memory and Modernization”

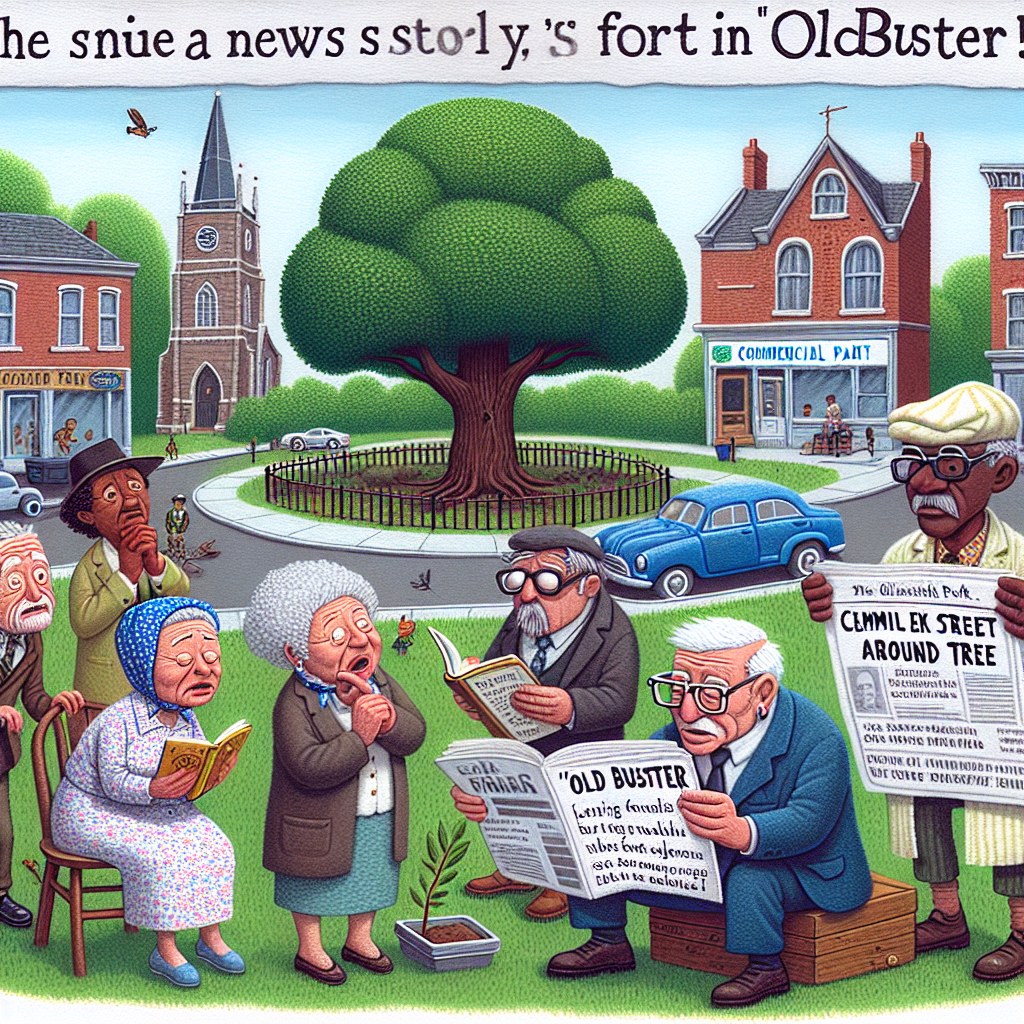

Chesterburgh’s beloved Elm Street Park, home to an aging oak tree everyone calls “Old Buster,” has sparked more chatter this week than the town’s annual chili cook-off. The oak, which locals swear has seen more anniversaries than the mayor’s been in office, might be uprooted—or worse, chopped down—under a city plan to “modernize” the park. What’s got everyone’s knickers in a twist isn’t just the loss of a century-old tree. It’s the suddenness of the announcement, the thin details on the so-called improvements, and the unmistakable scent of a development plan lurking under the freshly painted canopy.

Old Buster isn’t just a tree. At a rough count, it’s hosted dozens of school picnics, first kisses, and bark-carving afternoons. “I was here when my granddad planted that seedling,” said Martha Glenn, 78, sitting on a bench shading away from a late-afternoon sun. “Feels like someone’s trying to wipe a whole chapter of the town's memories.” Her jaw tightened when she added: “They say it’s for ‘community wellbeing.’ I say it’s for money, plain and simple.”

City Hall spilled out the news last Thursday with a press release as glossy as a magazine ad but far less clear. The proposal outlines adding “modern amenities” like new walking paths, fitness stations, and “interactive art installations” meant to “engage all generations.” But nowhere in the official documents is there a concrete explanation of how Old Buster fits into these plans—or if it does at all.

I dropped by the Parks and Recreation office for clarification. The spokeswoman, a perky newcomer named Lila Torres, brushed aside the oak question with a “We’re still gathering community input” line that felt more like a stall than a promise. “We want to hear from everyone,” Torres said, her smile unmoving. “The park will be a space everyone can enjoy.” When pressed about whether Old Buster will stay, she added an almost contradictory, “All options are on the table.”

“All options” is the language that sets old-timers on edge. Around here, it typically means one thing: the tree’s days are numbered if the bottom line demands it. A zoning change filed quietly last month confirmed whispers that the park won’t just ‘modernize.' The parcel may be subdivided, allowing for a small commercial spot for a café or boutique near the park’s southern edge. The permit application is thin enough to skim over but detailed enough to spark suspicion among those who know the lay of this sometimes muddy land.

I met Bill Tansey, who runs a secondhand bookshop a stone’s throw from the park. He called the whole plan “a Trojan horse disguised as progress.” Bill’s not in the habit of spinning tales. He pointed out that the shop's main windows face the park and the oak itself. “If they cut down that tree,” Bill said, voice low with the weight of long-held concern, “it changes the whole character—not just of the park but this whole block. It’s good for a sale? Maybe. Good for us? No.”

On Saturday morning, I found a handful of neighbors around Old Buster, standing in a loose circle like a quiet protest. Patricia, a retired schoolteacher and poetry lover, read a few lines she’d written inspired by the tree. “It’s not just wood and leaves,” she said softly. “It’s a keeper of stories, a silent witness. What happens when the witness leaves?”

These voices aren’t just nostalgic; they’re pragmatic, too. Local environmentalists point to Old Buster’s ecological role—a mini-habitat for birds, bees, and small mammals nestled in downtown Chesterburgh’s expanding concrete breath. The tree’s suppression could set a domino effect on the local green canopy the town so often brags about during festivals.

But city officials are keeping their cards close. No public forums have been scheduled despite the growing murmurs. Emails to the mayor’s office about a formal meeting have gone unanswered, and the next town council session doesn’t list the park’s fate on th