**"Seven Scooters, One Town: Chesterburgh’s Uneasy Ride Between Past and Progress"**

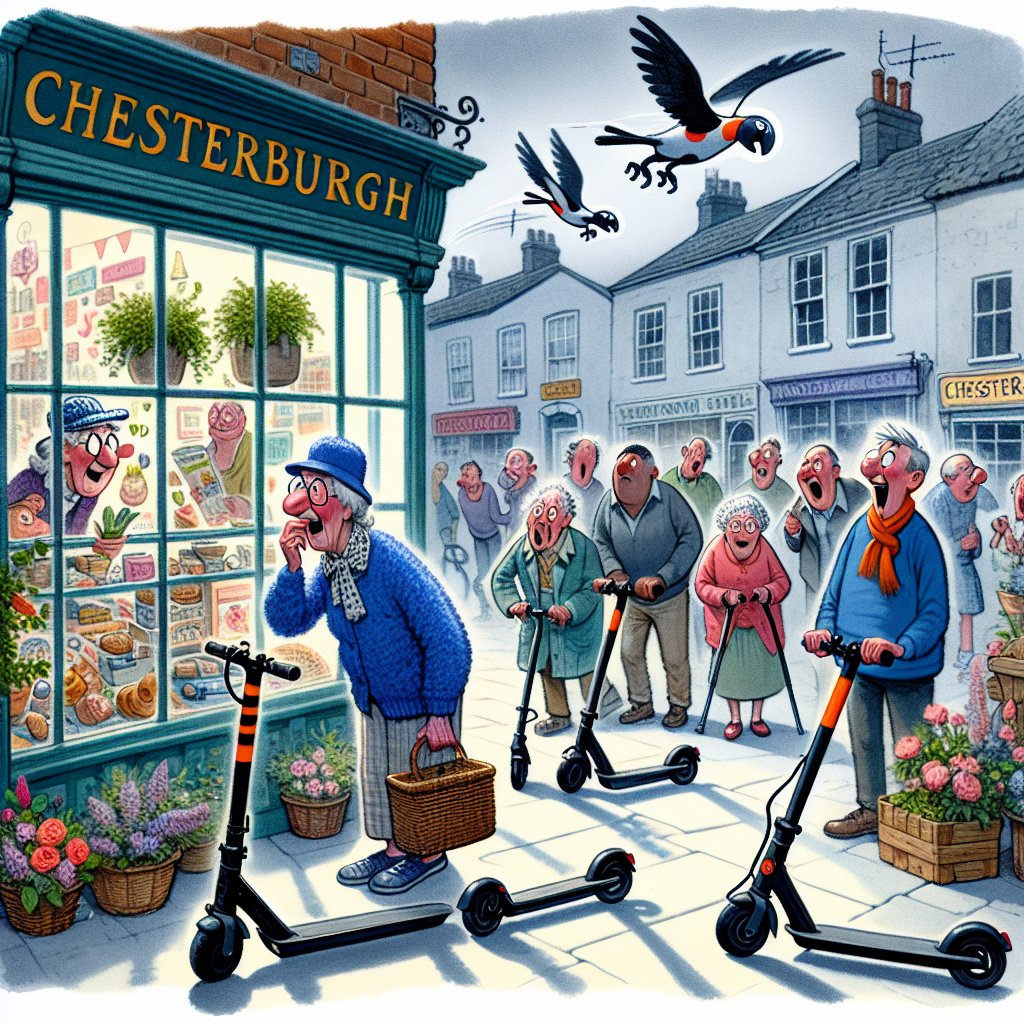

Chesterburgh’s sidewalks have long worn thin with the slow shuffle of familiar footsteps, but last Thursday, a strange new rhythm clattered its way through the town square. It came in the form of a fleet of seven electric scooters, freshly parked and gleaming under the cautious spring sun. They appeared as if summoned by some tech-savvy courier service—or perhaps a rogue entrepreneur staking claim on Chesterburgh’s sleepy streets. No announcements preceded them, no town hall nods or zoning whispers. Just seven scooters that weren’t here yesterday, and maybe won’t be tomorrow.

These scooters are the newest chapter in Chesterburgh’s quiet tension between progress and preservation—a tension I’ve watched simmer for years with the detached interest of someone who’s seen too many bright ideas flame out under the weight of local stubbornness. “They’re clutter,” said Marge, the woman who’s been running the corner flower shop for thirty years. “Like those damn bikes that no one ever uses but never moves.” Marge’s flower shop window is a map of history, cluttered with decades of postcards and wilted memories, and she guards it like the last good thing in town.

Yet, the scooters zipping around do bring a kind of energy to the square that the usual Saturday morning farmer’s market can’t match. Little kids eye them with the same mix of curiosity and skepticism as their parents. Elderly couples cross the street with the practiced wariness of people who remember what the town looked like long before the word ‘gentrify’ even drifted here on a breeze. Even the town’s janitor, Pete—a man whose conversations usually revolve around the alleged virtues of his old vacuum—nodded thoughtfully as one whizzed past. “They’re noisy, but I guess they’re here to stay,” he muttered, a concession that spoke of countless battles lost elsewhere.

How these scooters arrived without fanfare is a question that has set Chesterburgh’s rumor mill spinning faster than an espresso machine in the early morning. Town officials are mum, dusting off their usual scripts about “review processes” and “public safety evaluations,” but press releases have not yet materialized. “We have no formal record of any permit applications for this device fleet,” confirmed a city clerk who asked to remain unnamed, a tone of puzzlement threading her words.

The lack of official acknowledgment hasn’t stopped the scooters from becoming a talking point—or a thorn—in the side of local residents. On Main Street’s West End, Nancy Baker, an outspoken advocate for the preservation of the town’s historic character, declared, “It’s just another sign that the town council doesn’t listen. You give an inch to progress, and it’s a mile of concrete before you know it.” Nancy’s sentiment echoes the collective memory of dozens of similar battles: a convenience store resisted here, a chain coffee shop granted a permit downtown despite protests there. The scooters, she fears, are just another stepping stone toward erasing the small-town soul Chesterburgh’s kept alive for two centuries.

Yet, not everyone sees the scooter saga through a nostalgic lens. The post office’s new young clerk, Jamie, thinks they are “a sign that the town’s finally trying to catch up.” “My neighbors think it’s unsafe, but honestly, I love the idea of getting around without waiting for the bus,” Jamie said, adjusting the bright blue scarf that seemed to shout ‘urban’ in a town where subtlety is a virtue. For people like Jamie, who moved to Chesterburgh only last year, these scooters represent a crack in the rigid shell of an otherwise slow-moving town.

And then there’s the question of who owns the scooters. Local entrepreneur Simon Graves, known for his chain of artisanal coffee shops, quickly stepped forward to deny any association. “Not me. Doesn’t fit my brand,” he said, his grin quick and somewhat rehearsed. He went on to speculate that they might be the work of a nearby univer